male genital exhibitionists on mediæval churches

beard-pullers

in the silent orgy

ireland

& the phallic continuum

field

guide

to megalithic ireland

the

earth-mother's

lamentation

beasts and monsters of the mediæval bestiaries

links

to

ENGLISH FEMALE EXHIBITIONISTS ON A FRATERNAL SITE:

Ampney Saint Peter Gloucestershire

Austerfield Yorkshire

Bilton in Ainsty Yorkshire

Binstead Isle of Wight

Buckland Buckinghamshire

Croft Durham

Cynghordy Carmarthenshire

Easthorpe Essex

Fiddington Somerset

Holdgate Shropshire

Kilpeck Herefordshire

Llanhamlach Brecon

Llanon Dyfed

Penmon Anglesey

Romsey Hampshire

Royston Hertfordshire

Saintbury Gloucestershire

Stoke-sub-Hamdon Somerset

Twywell Northamptonshire

Wimborne Dorset

Winterbourne Monckton Wiltshire

Wolston Warwickshire

Map

of most figures in England,

Scotland and Wales

List

and distribution map

of Irish

exhibitionists

APOTROPAIA,

apotropaic:

The erection, representation, display and use of often grotesque figures and objects to protect against or ward off misfortune, thieves, enemies, sorcery, witchcraft, evil spirits, bad luck or the Evil Eye.

The simplest examples in Nature are protective false eyes, whose forerunners in evolution were the eye spots developed by some hexapods to encourage predators to think they were being watched by their quarry.

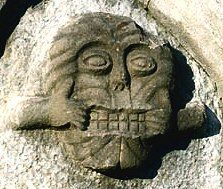

By far the oldest (universal) human behaviour patterns and displays are the protective hand, beard display, breast presentation, pulling a face or mouth-pulling, genital and pubic display, arse-display, presentation of a grotesque mask, milk-squirting, erection of 'sentinel' or guardian figures, and sticking out the tongue.

From

Sermons

in Stone

to the Petrified Hag

female figures - part II

|

Sheela-na-gigs (even the Rahara figure above) are quite different from the highly-sophisticated and fine carvings that appear on misericords, which very often are satires on people and morals: defecating monks, talking donkeys, as well as depictions of fruit and vegetables (even the humble turnip), foliate masks, labours of the months and so on - but almost never genital exhibitionists. Crucially, they were not for public view but commissioned (or gratuitously carved) by men out of whimsy or out of a desire to make a comment upon society, morals or the deacon who was to use the misericord. In the very late Romanesque churches of Poitiers, exhibitionist and other minatory carvings have moved to internal corbel-tables. Then they disappeared altogether or translated to roof-bosses, misericords and bench-ends, losing their instructive qualities to become jeux d'esprits, satires and whimsies.

Anal exhibitionist misericord (male), Rodez

Cathedral (Aveyron):

Female head-to-ears anal exhibitionist acrobat on the Romanesque church at Montmoreau (Charente)

For example, some Irish figures are, interestingly, placed sideways, on quoins (e.g. Kiltinane Church, above) and some Irish figures are on castles (e.g. Tullavin Castle) - again, sometimes on quoins. The sideways placing goes back to the 12th century, when a (non-exhibitionist, seated, cloaked) figure from the 10th century was re-used in the church on White Island, county Fermanagh, and another (a female exhibitionist) was placed as if it were an abacus without a capital in the doorway of Liathmore church, county Tipperary. This symbolic position in Romanesque art indicated vanquishment and humiliation, and it is quite possible that this symbolism was consciously retained through the Middle Ages. Cloghan[e] Castle (Roscommon)

photographed by Gabriel Cannon. Several Irish figures are above or beside doorways (e.g. Ballinderry Castle), while others are from 5 metres (e.g. Ballynacarriga Castle) to around 20 metres above ground level, as at Garry Castle (below). Other Irish figures were carved on free-standing stones (as at Tara), placed on old town walls, and, finally, incorporated into town-houses. Drogheda (Louth) before removal to the town museum. click to enlarge In Britain the figures are almost all on churches. On only one of those churches - at Rodel on the Hebridean island of Harris - is an exhibitionist figure placed sideways - but not in the same manner as the Irish carvings, and not on a quoin - and not female. In both Britain and Ireland many of them have obviously been crudely inserted into pre-existing buildings, often being trimmed or cut away to do so. Perhaps the most dramatic example of this is at Whittlesford in Cambridgeshire, where a stone panel has been refashioned to form a window-top. Whittlesford (Cambridgeshire). click for a high-resolution enlargement. Sheela-na-gigs were first noticed by the literate in Ireland (1840), and hence have been thought of as Irish in inspiration and 'Celtic' in origin. The term itself is shrouded in controversy, and a bogus Irish etymology - Síle na gCíogh (pronounced 'sheela-na-ghee' and meaning 'Sheela of the Paps') - was adduced. But the paps, though obvious in some examples, are not present in many, and the most obvious feature is the vulva. Gig or Geig is actually dialectal Northern English for vulva - and, elsewhere, for boat - so it is ironic - though typical - that an Irish origin for the carvings as well as the name obsesses most people interested in this bizarre subject. Giglet was a word describing a giddy or wanton girl. When the first example (dancing a jig) was described in 1840 (on Kiltinane Church, county Tipperary) the term was already widely known and used. But it was not applied to all figures - which had such names as Síle ní Dhuibhir (Sheela O'Dwyer), Sheela ní Gara, Sheila-na-giddy, and (on Moycarkey Castle) Cathleen Owen (see below). Recently, an alternative origin has been suggested: Shee (Sídhe or its modern form Sí in Irish), lena (meaning 'with her') Gig (vulva or female genitalia). Unfortunately, not only is the construction awkward in Irish, but the primary meaning of Sídhe is Mound or Tumulus, where Otherfolk dwelt. Non-Irish-speakers have mistakenly assumed that the word meant fairy, goblin, sprite or earth-spirit. Barbara Freitag claims that Sheela-na-gigg was also a jig-like dance which began in Scotland in the 17th century, but did not get to Ireland until the 18th. It was a kind of slip jig, and, though by then not a dance (like the Volta of Elizabethan times and Waltz in its first years) considered obscene by the polite, it may well have been an Invitation to Lewdness amongst the peasantry, as it was generally in Shakespeare's time: "It

may be hard for us to conceive of the conclusion of Shakespeare's

Romeo and Juliet The first Irish exhibitionist carving to be recorded - the figure on Kiltinane Church - is in a pose reminiscent of Indian (or Middle-Eastern) dance. A more tangible connection with India may consist in the mysterious objects and ill-defined masses beneath the vulvas of several sheela-na-gigs (e.g. Dunnaman), which resemble the menstrual flux of the goddess Kali in many South Indian sculptures. Note the spelling: gigg. This suggests that the word was pronounced 'jig' and was thus pronounced in Ireland, and almost certainly with regard to the sheelas. But everyone pronounces the phrase with a hard g or a gh. Now compare the phrase jiggery-pokery, which was a word applied to rapid or desperate sexual liaisons. Jig-a-jig is a term which survives to this day in West Africa, from the sailors in days of yore and today, and to jiggle was Victorian slang for to fuck. In the 18th century there was an Irish ship out of Cork known as the Shelanagig. It later took part in naval action with the British West Indian fleet during the American war of independence. Think also of 'dirty postcards' (see page three). Then there is the likelihood that the 'mumbled' word recorded at Kiltinane was misheard., when a local man, reportedly asked about a 'lewd figure' on the ruined church at Rochestown, mumbled that It's just an oul' sheela-na-gig. Apart from that, the light horse-drawn carriage known as a gig was sometimes spelled jig, indicating that it was pronounced with a soft g. Linguistically, hard G and J are interchangeable in Indo-European languages. The Etymological Dictionary Online lists quite a few forms and meanings of gig, however pronounced: giog,

fizgig : fizzy or frivolous woman As already mentioned,

other terms have been recorded: Shelagh or Sheila was also the folkloric "wife of St Patrick" - but of course it was also used, as still in Australia, as a generic term for 'woman'. Joseph-Gustave

Witkowski's L’Art

profane à l’église (1908) refers to

Julie la Giddy. Giddy (hard G) he translates as femme

publique, 'woman of the streets'. But the word is mainly used

to describe dizziness or vertigo (such as one might have after

dancing, for example: a jig : Jilly the Dizzy.) A frisky horse

can also be called giddy, hence the exhortation giddy-up

to make a horse go faster. His translation of Shelagh as Julie is interesting. The Etymological Dictionary Online reports that "Shakespeare used the word flirt-gill (i.e. Jill) "a woman of light or loose behaviour" (Fletcher formalizes it as flirt-gillian), while flirtgig was a 17th century Yorkshire dialect word for "a giddy, flighty girl." Gill-flirt, giddy young woman" is from 1630s." [My emphasis]. Flirtgig (soft G) might suggest that exhibitionism was an extremely 'fizzy' form of flirting. So In the hyphenated term both elements may refer to whorish or outrageous behaviour. * The most important - indeed cataclysmic - social event between the dawn of the second millennium and the religious wars which followed the Reformation was the Black Death, the plague which in its various forms killed a quarter of Europe's people. One of the results of the Black Death was that the Christian god began to be mistrusted, for ordinary people considered that the Church's doctrine that its teaching would save believers (or even just those who entered the portals of a church) was obviously false. Thus began the rise in importance of the Devil (a figure deriving as much from Persian as from Greek mythology) who could so easily become the ruler of the world in an antinomian struggle recalling the beliefs of the Manichæan Cathars who were wiped out in the terrible pogrom known as the Albigensian Crusade at the beginning of the 13th century, shortly before the infamous Fourth Lateran Council. With the new belief in the Devil came a belief in 'witchcraft', which could include any folk-practices which seemed to by-pass or cock a snook at the Church. So a decline in metaphysical awareness results, as Eliade remarked (above) in an increase in superstition. This in turn made the Church more hysterical in its fear of 'heresy'. During the Black Death a new motif became popular in European art: the Dance of Death - most famously portrayed in our own day in Ingmar Bergman's film The Seventh Seal.

Many of the skeletal ones are, however, not dancing. And what about the huge vulvas even of those which are dancing ? They have nothing to do with the Dance of Death. On the one hand they derive directly from Romanesque female exhibitionists. On the other hand, they seem to be saying something about this life before death, perhaps life after death, and female fecundity - perhaps social anxieties surrounding female fecundity or the lack of it, or the high toll of still-births and deaths in labour. Moreover, whereas the torsos are emaciated or skeletal, some of the vulvas are anything but - though others are merely slits, grooves or holes. The very large vulvas might well indicate dilation prior to birth - in which case the figures might be 'birthing-stones' resorted to in order to help in childbirth. Right up to the twentieth century death of child and/or mother during or just after parturition was a common occurrence. But the question arises: when Romanesque exhibitionists occur all over Europe from Sicily to Denmark and Ireland to Bohemia, why do these late, crude figures hardly occur at all outside Britain and Ireland ? And if the large vulvas and labia do indicate pre-parturition dilation, this chimes with the Romanesque function of images of Luxuria as warnings against consequences - in this case unwanted pregnancy rather than Hellish torment. The Cavan figure (above) is one of only very few to have an open mouth and a tongue reminiscent of Romanesque tongue-stickers (which in turn recall Classical Gorgon/Medusa heads - see Ballintubber Abbey, county Mayo - and Indian representations of Kali). More germanely, it recalls the statue from Lusty More Island and the female side of the double-sided male-and-female statue at Boa Island not so far to the North. Caldragh Graveyard, Boa Island (Fermanagh): female side of double figure. The male side of this statue is ithyphallic, and there is a certain indefinable similarity between the Boa Island figure and the "Sky-Father/Earth-Mother" carving at Whittlesford. People have seen a connection between acrobatic feet-to-ears exhibitionist figures and this one - but it is more likely that the crossed limbs are arms. A more apparent similarity is that between the Boa Island figure and French Romanesque (12th century) carvings, like one at Bussières-Badil in Dordogne. The genital area of some accessible figures (but not those on Boa Island) has been rubbed. But other figures have not been touched. Were they carried about like statues of saints and shown to pregnant or barren women, as were figurines, statuettes, magic sticks, stones and pebbles ? Were the rubbed figures always rubbed, or did they acquire a new or secondary quality ? Some rubbed figures are not sexually exhibitionist but, like the Kilsarkan (Kerry) figure below, have been listed among the sheela-na-gigs in their many and lengthening inventories.

Kilsarkan Church (Kerry.

A couple of carvings (Lavey Old Church, Copgrove in North Yorkshire, Church Stretton in Shropshire) are holding circular objects which could be 'birth-girdles' - instruments of sympathetic magic used world-wide to help ease childbirth by being unloosed and/or removed at the beginning of labour. Other figures (e.g. Ballinderry Castle) have indefinable masses between their legs - which have variously been interpreted as stools, phalluses, foetuses and afterbirths, but which I have already proposed as menstrual flow. Figures high up on walls could not, of course, be rubbed. Some cannot even be seen clearly. These are not all later inserts, so they were intended to be high up. The church at Stanton St Quintin (Wiltshire),

whose sheela-na-gig on the tower An apotropaic (evil- or danger-averting) function has been suggested for such figures. But the tradition of gorgon-heads, penises and vulvas as seriously apotropaic seems to me to be more literary fancy than a reflection of actual practice, despite the perhaps unique male example at Bolmir, near Cervatos, who is making the "fig" gesture which is both obscene and apotropaic. Whatever lucky charms might be worn - or recited - few people could have imagined that a female exhibitionist would make a cruciform church even more apotropaic, or a castle less likely to be captured. And there is the simple matter of rape: how apotropaic is the vulva when rape is the commonest crime ? Clenagh Castle (Clare). Some lower figures were considered to have power to induce fertility. These include the sheelas at Rosnaree and Ardcath (Meath), Clenagh (above), and Holdgate in Shropshire. Cattle used to be driven past the carving beside the door of the now-wrecked Blackhall Castle in Kildare - just as cattle were driven between pairs of (male and female) standing-stones. The Pennington figure in Cumbria was locally known as Freya - the Norse goddess of fertility - though this might have originated as an antiquarian's conceit.

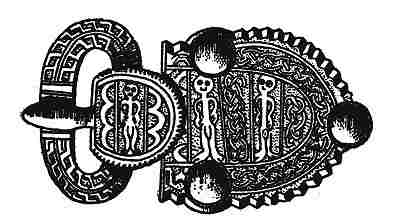

Merovingian (7th century) bronze buckle-plate

from Picardy: a talisman or fertility-charm The obvious insertion (and trimming) of some in churches has led people to suggest that the local clergy had decided, in a long tradition going back to Roman times, to incorporate them and their 'power' rather than vainly to challenge or fight against whatever purpose(s) they served against the Church's perceived interests. Worshipped wells were christianised throughout Europe, and quite a few standing-stones, too, especially in Brittany. As already mentioned, the sheelas adopt various stances and attitudes. Some have their right hand to their right ear (Tullavin Castle, Clonmacnois 2, Portnahinch Castle and the red-painted figure from Behy Castle).

Behy Castle (Sligo) photographed by Gabriel Cannon. Some raise their left arm to touch the left side of the head (Ballynaclogh Castle, Kiltinane Church, and Kirkwall in Orkney). Some raise their left arm to brandish a slim object (Killeagh, Fiddington - and compare the fish brandished in both raised hands at Rochester). Some hold an object in an unraised left hand (Tugford, Seir Kieran) or on their left arm (Lavey) or under their left arm (Lixnaw).

Small figure from Lixnaw (Kerry). To try and categorise them in the hope that something thereby will be revealed is pointless. Categorisation was an obsession with Victorians and Edwardians, and has merely lost the study of sheela-na-gigs in a maze of anomaly and puzzlement - recently vitiated further by 'students' of 'Gender Studies'. However they might be grouped (and the distribution of the various types that people have assigned is remarkably even across the British Isles), there are doubtful members and exceptions. And if some might tentatively be designated as magical aids to fertility or labour, others cannot - especially the remarkable Whittlesford sculpture. But serious and significant they all were, and had absolutely nothing to do with pleasing the eye. Are they 'ugly as sin' or 'help from beyond' - beyond the bounds of ordinary experience, beyond the grave ? Or both ? Or more ?

Adam and Eve on a capital of the late 12th

century church ...and the well-known exhibitionist corbel on the same church.

Gorgon at Corfu (Greece) There is also an iconographic connection between sheela-na-gigs and snake-haired (or snake-girdled), tongue-protruding Gorgon-figures, via such carvings as the Poitiers (Saint-Hilaire) capital and a magnificent toothy snake-spewer at Ballintubber Abbey in county Mayo. At Chalais (Vienne) a feet-to-ears anal and vulva-pulling exhibitionist acrobat is placed beside a capital of two heads, one of which is spewing snakes - likely to be a depiction of calumny or blasphemy.

It is surely no coincidence that the biggest concentration of Romanesque carvings of wealth/luxury/sin motifs occurs in Western France, as above - specifically Aquitaine. This is precisely the area where the Romantic-Chivalric Troubadour fantasies of 'Courtly' Love were fostered and purveyed. It seems to me that the Benedictines and Augustinians were pointing out that the Romances were deceptions by Satan : Sex is Sex, but Love belongs to God. The idea of the damned person suckling (or in the case of males, having his genitals attacked by) snakes throughout eternity produced variations. Other 'unclean' beasts appear on representations of the punishment of Luxuria: specifically, toads and tortoises. In the Musée Fenaille at Rodez (Aveyron) is a statue described as a Gallo-Roman "Dancing Venus" which could date from any time between the 5th century BC and the 5th century of the present era. She wears clothes resembling those of a Roman matron and holds her long tresses in the manner of many sheela-na-gigs and Romanesque exhibitionists. To her left is a serpentine monster. On one of the narrow sides of the stele or slab is an almost-effaced standing male figure. Such a carving is a very likely source of inspiration for Romanesque sculptors.

Castletown Castle (Louth

I have not mentioned the Celtic Deity theory fashionable among the fashionable Celtophiles of the last 40 years of the 20th century. Needless to say, only a few - and not even definitely exhibitionist - figures (on pillars like those at Tara and from Swords) could possibly date from pre-Christian times. This one has been interpreted as Lugh of the Long Arm. Figure on standing-stone at Tara (Meath). Theories which insist on an Old Religion surviving into mediæval times complete with stone idols are not only unprovable, but, frankly, ludicrous - since Celtic religion was very phallocentric, and the landscapes of the British Isles which feature rounded hills in the form of reclining women or their breasts are littered with phallic rather than cunnic or egg-shaped stones. (The Turoe Stone in Galway has ornamental sperm undulating over it.) Even holed stones are rare. And why would goddess images suddenly appear out of nowhere, when the Catholic church had realised as early as the 12th century that it was lacking in this respect, and had instituted a rapid and successful campaign to make the Virgin Mary into an all-powerful quasi-goddess, a direct intercessor with God ? Since human figures in attitudes of sexual display occur world-wide in cultures ranging from Neolithic Malta, the Neolithic Northern Balkans and the Baltic, Classical Greece (the 'Baubo' figures) to mediæval and modern India, SE Asia and modern Africa, these forerunners and parallels are something of a red herring, and do nothing to explain why they are so widespread in late-mediæval Britain and Ireland. However, recent finds of small gold figurines at Smørenge on the Baltic island of Bornholm bring the motif a little nearer. The fragile object below is of pressed gold foil, and weighs only 0.1 g.

But the hands are significantly resting on the knees in a more or less regal position, so it is highly likely to be a votive offering or an amulet. As for another - but solid - gold object found close by, it seems to be an item of jewellery, possibly a hair-clip, bearing little relationship to the sheela-na-gigs of the British Isles. Other finds at Smørenge include trousered male figurines in pressed foil. All are thought to be from around 500 AD.

This web-page has simply summarised the problems associated with any attempt to 'interpret' sheela-na-gigs - which are, perhaps, to be compared with what used to be termed 'junk' DNA: an inexplicable part of our inheritance.

|

| continued on |

LIST

of PHOTOGRAPHS of MALE and FEMALE EXHIBITIONISTS

on this site, outside this text

with distribution map.

List

and distribution-map of Irish

exhibitionists

Map

of most figures in England,

Scotland and Wales