THE INDIAN INFLUENCE ?

Column-swallowers,

kirttimukhas, kalas

and foliage-spewers

male

genital exhibitionists

on mediæval churches

beard-pullers

in the silent orgy

ireland

& the phallic continuum

field

guide

to megalithic ireland

the

earth-mother's

lamentation

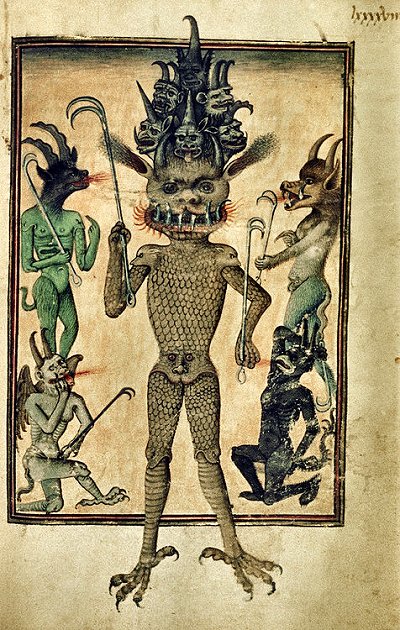

beasts and monsters of the mediæval bestiaries

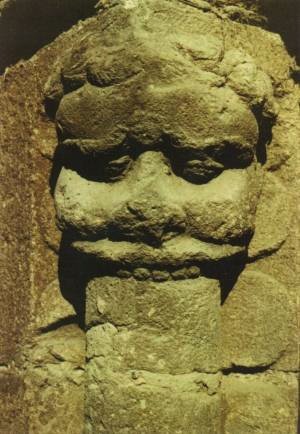

Romanesque 'cul-de-lampe' beneath the dome of the

12th century church at Civray (Vienne).

|

Door-capital, Puente la Reina (Navarra), Spain

Some French observers have thought that column-swallowers represented Gluttony - but they are too decorative to be sinful and there are no accompanying agents of retribution such as are often associated with representations and symbols of sin.

A monkish column-swallower, priory of Bruère-Allichamps (Cher)

It was only on reading Mercia MacDermott's excellent EXPLORE GREEN MEN (Heart of Albion Press, 2003) that I began to see that the image of the column-swallower was closely allied to that of the Foliage-spewer (one of the types of 'Green Man'), to which Mercia MacDermott convincingly attributes an Indian origin. The earliest known Western Christian example of column-swallowers/spewers appear, like the male exhibitionist, in an Anglo-Saxon manuscript (British Library Harley 76, f.8v, f.10). Significantly, they are upside-down on two of four columns separating Canon Tables (of New Testament concordance). They are spewing or swallowing the groins of vaults. None that I have seen in stone do this: they disgorge or engorge the columns, a more practical arrangement and more satisfying to the eye. This strongly suggests that the illuminator of the manuscript had not seen an example in stone now lost or destroyed. The earlier or contemporaneous Book of Kells has an arch-biting beast extending from a canon-table column, which may also be an inspiration - as of course are the beasts which bite the ends of large initial letters on manuscript pages. The motif is unknown in Classical art - like the Foliage-spewer whose earliest manifestations in stone are early or immediately pre-Romanesque (e.g. a 10th century font at Guarbecque in the Pas-de-Calais which has two beast-heads spewing foliage on two of its corners). Foliate masks and heads are, of course common in Classical art, the head of (or crowned by) leaves being associated with deities, especially those associated with woodland and forest. Although a head on the 4th or 5th century sarcophagus of Saint Abre in Poitiers has tendrils of foliage issuing from its nostrils via a small pair of cornucopiæ, it is not really a foliage-spewer in the way that hundreds of Romanesque and post-Romanesque carvings are. Apotropaic, tongue-protruding Medusa or Gorgon heads with writhing snakes were also common in classical times. In the church of Saint-Hilaire in Poitiers is an eleventh-century snake-spewer, which might be a forerunner of the foliage-spewer and linked to the pictures of evil people spewing toads in the 9th/10th century Spanish "Beatus" commentary on the Book of Revelations.

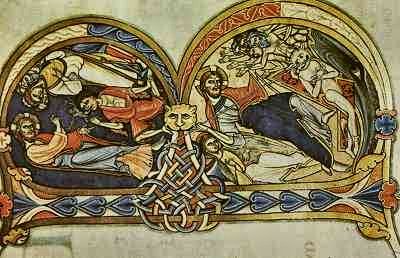

The above example on a font in Lullington (Somerset) is one of a band of linked foliage-spewers, while the example below from the 12th century Winchester Bible shows a highly-decorative feline head separating two Biblical scenes - one of which (on the right) is the Harrowing of Hell or the overthrow of Satan by Christ.

Foliage-spewers occur as frequently on roof-bosses as on capitals, and the example below, also 12th century, can be seen under the entrance-archway to the chapter house at the Abbey of St George, Saint-Martin-de-Boscherville (Seine-Maritime). It has a humanoid head, and apart from the stylised foliage issuing from a jawless mouth, there is also the upside-down-pine-cone or bunch-of-grapes motif which Mercia MacDermott shows to have originally been the lotus bud associated with kirttimukhas - demons which appear in various different Hindu and Buddhist myths and legends - in India and South-east Asia.

(It is not a pineapple, which is a South American bromeliad.) The poetic term kirttimukha means Face of Glory, and kirttimukhas have monstrous (often feline) faces, with bulging eyes and a wide mouth (usually jawless) swallowing foliage, flowers or ribbons of beads - an attribute they borrowed from a much earlier motif, the foliage- or lotus-spewing makara, a mythical sea-monster with which they often appear.

The two motifs are conflated and confused: the images above came from the Web when I typed kirttimukha in the Google search-box. Both were labelled makara. Explore Green Men, however, provides a fifth-century example from Cave n° 1 at Ajanta which shows the two type of monster/demon engorging and disgorging necklaces or beads, between which is a stylised lotus-bud.

Foliage-spewing beast (shown upside-down) at Montmoreau (Charente)

Bearded seated figure flanked by two kirttimukha-like lions at Neuvy-Saint-Sépulcre (Indre)

A bicorporeal dragon (symbolising Hell ) swallowing a damned soul at Civaux (Vienne)

Outside India, demons known as kalas are frequent in Thailand, Cambodia and Indonesia. They appear often over the doorways of entrance pavilions as Guardians with disembodied head (compare the Boscherville roof-boss above) and bulging eyes, a frightening row of upper teeth, and (not always) ribbons of flowers, foliage or pearls disappearing into their open mouths. The mythic kala devours all in his path, serving as a reminder that everything in the natural world - represented again by the foliage - is eventually consumed by time. Thus, like kirttimukhas, they are associated with eclipses and referred to as (amongst other things) sun- or moon-eaters, and - intriguingly - Devourers of Time. Outside India, demons known as kalas are frequent in Thailand, Cambodia and Indonesia. They appear often over the doorways of entrance pavilions as Guardians with disembodied head (compare the Boscherville roof-boss above) and bulging eyes, a frightening row of upper teeth, and (not always) ribbons of flowers, foliage or pearls disappearing into their open mouths. The mythic kala devours all in his path, serving as a reminder that everything in the natural world - represented again by the foliage - is eventually consumed by time. Thus, like kirttimukhas, they are associated with eclipses and referred to as (amongst other things) sun- or moon-eaters, and - intriguingly - Devourers of Time. This one (below) is from Banteay Srei, part of the vast Angkor complex in Cambodia.

..while the Kala above grips the tendrils snaking out of the sides of his mouth from behind amazing teeth with very human hands.

Details of doorway, Saint-Hilaire-la-Croix (Puy-de-Dôme) Kalas are associated with Shiva, for one legend attributes the birth of an original Kala to Shiva's masturbation into the sea, where his semen was swallowed by a huge fish which gave birth to the sea-monster. Attempts by the gods to destroy Kala are unsuccessful until Shiva finally conquers him, as illustrated in the sculptures below at Prasat Narai in Thailand, and Bantea Srei, Cambodia.

In the tenth century, Vikings brought a Sasanian metal vessel, decorated with a Zoroastrian fire altar, from Iran to SW Scotland in the 10th century, as part of the Galloway Hoard in Kirkcudbrightshire. Moreover, it is important to realise that Hindu art is as symbolic as Romanesque Christian art, though the symbolism is, necessarily, different. Motifs travel very easily from one symbolic art to another, though the interpretations may be diametrically opposed. This accounts to some extent for the pervasive ambiguities of Romanesque art.

Detail of doorway, Chadenac (Charente-Maritime)

Detail of doorway, Civray (Vienne)

Detail of doorway, Périgné (Deux-Sèvres)

External capital, Villavega de Aguilar (Palencia), Spain

Nave-capitals, Cunault (Maine-et-Loire) The

last picture (above) returns us to the original subject of this

essay: the column-sucker.

Fritwell: photo © Ruth Wylie On the Fritwell tympanum is an iconographic confluence of all the themes mentioned here, and we can now see the enigmatic column-swallower in an iconographic context extending back to India in the third century BC. The connection is more luxuriously illustrated by this capital from Toulouse cathedral, now in the Musée des Augustins, and officially photographed by Daniel Martin.

The column-swallower (below) on a door-capital at Stanton-St-Quintin (Wiltshire) has a distinctly oriental appearance with its strange head-dress and protuberant eyes;

it and the significant examples at Puente la Reina (Navarra), Avington (Berkshire), Elkstone (Gloucestershire) and in Cormac's Chapel, Rock of Cashel (Tipperary) lack a lower jaw, just like a kirttimukha.

And one fine example of a column-swallower extends a disembodied foliate arm with a hand into its ear in a gesture reminiscent of some sheela-na-gigs. Door-capital, Saint-Romans-lès-Melle (Deux-Sèvres)

While we might regret that we do not know quite what the column-swallower "means", it is very exciting to notice and discover the parallels and possible influences - which almost certainly were not all known to the sculptors.

This capital at Javarzay (Deux-Sèvres) illustrates an interesting parallel.

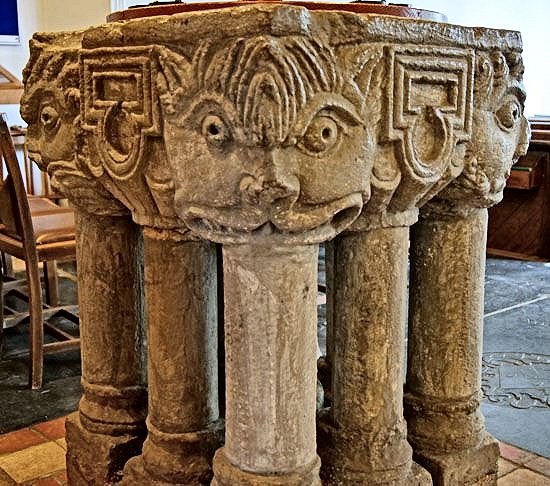

Afont at South Wootton (Norfolk). An extraordinary example in a Carinthian cloister

A very Oriental variation on the theme

at Echebrune (Charente-Maritime); Click for a large picture of another at Saint-Hilaire-la-Croix in Auvergne.

One of several column-swallowers on the high windows of the apse at Saint-Marcel (Indre) At Saint-Mary-Redcliffe in Bristol there are three or more column-swallowers without teeth, one of them feline but the others humanoid. This should be considered a natural development of the motif and a hint that perhaps a specific sin is illustrated. But should anyone doubt the influence of India on Romanesque sculpture, via the Muslim caliphates, they should consider the doorway of the 12th century church at Sant Joan de les Abadesses in Spain. Here, quite apart from very Indian looking masks and foliage, the elephants are depicted with amazing accuracy. . As late as the 18th century, few people in Europe knew what an elephant looked like, as witness Dr Johnson's entry in his famous Dictionary. In 1960 the American scholar Millard B. Rogers published a study of Indian influence on the Romanesque sculpture of the Pilgrim Roads between Poitiers and Santiago de Compostela. The curious and enquiring travelled the ancient routes over the centuries along with the merchants, monks and missionaries. And we should not forget that Ireland, which had a brief but decisive cultural influence in Western Europe way beyond its size and sophistication, was more remote and inhospitable to the subjects of the Byzantine Empire than was India. Sant Joan de les Abadesses (Girona)

Three of six magnificent triple transept-capitals, Colombiers (Vienne)

Saint-Savinien (Charente)

Izon (Gironde)

Mathieu (Calvados) repainted

in the 19th century Click

to see column-swallowers

Another late adaptation of the motif. |

Below are links to three articles about connections between Anglo-Saxon England and Southern India.

King Alfred sent a delegation to the sub-continent in the 9th century.

https://www.caitlingreen.org/…/04/king-alfred-and-india.html

http://scribbled.wikidot.com/sighelm

http://www.peppertrail.com/inner.php?menu_id=3&sm1_id=30&index_id=1

What are we to make of this 15th century carving at Candi Sukuh

in Java

which, apart from the typical Hindu hair-style, could have come from

a 12th century church in France ?

Rappach (Baden-Württemberg, Germany),

photographed by Emil Bock

Crowland Abbey, Lincolnshire, photographed by Tina Negus.

More photographs of column-swallowers

all © and by courtesy of Tina Negus:

| • Pons

(Charente), Passage

Saint-Jacques • Pouzauges-le-Vieux (Vendée), painted interior capital • Eastleach Turville (Gloucestershire) • Ledbury (Herefordshire), North Door |

Sigogne (Charente)

![]()

Click to download from the Web:

ANIMAL

SYMBOLISM IN ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE

by E.P.Evans

an excellent and comprehensive book

from

![]()

and read an article on

the 'Green Man' in colonial African art

included

in this CD-ROM.